Lockheed Martin's Q3 performance reveals a narrative of surface-level success masking potentially deeper challenges with the investment case. While topline numbers beat expectations, the company's 2025 guidance exposes fundamental uncertainties—particularly around the F-35 program and pension dynamics. These variables don't just represent minor fiscal complications, but signal potential constraints on the company's free cash flow generation, challenging the market's baseline assumptions about Lockheed's FCF potential

Lacklustre Guidance

Despite very strong order growth, Lockheed will remain a low-to-mid single-digit growth company through 2025. The company expects low single-digit revenue growth through to 2027. It also highlighted that should supply chain bottlenecks subside, growth could improve towards a mid-single-digit opportunity. As Lockheed Martin has a very diversified portfolio, it lacks the leverage to specific areas of spending. Stronger growth areas, like missiles and the F-35 program, are being diluted by the wider portfolio. In addition, Lockheed's growth narrative has devolved from program execution to strategic ambiguity. What was once a clear investment thesis—driven by specific execution on high-value defense contracts (the F-35)—has blurred into a landscape of uncertain potential. The broader defense spending environment suggests opportunity, yet Lockheed appears unable to translate macroeconomic tailwinds into a compelling, differentiated growth strategy.

Questions also reigns over Lockheed's outlook for margin improvement. The company expects 10 basis points of improvement in segmental margins annually to 2027, with the possibility of 20 basis points should programs become de-risked from a cost perspective over the coming years. The issue we have with the margin framework is the complete lack of detail the company can share with investors. As most cost overruns have been due to classified projects, Lockheed cannot give guidance on the full amount of cost overrun, the timing or end of the contracts, let alone any detail on the nature of the margin pressure it has seen. The one detail we had from management did not fill me with confidence.

Lockheed’s CFO, Jesus Malave, Jr., commented: “I can tell you is that we are essentially meeting our scheduled objectives, albeit at a higher cost. And I would say the cost is really a function of the aggressive pricing that we bid originally.”

Aggressive bidding represents more than a financial tactic—it's a strategic gamble where uncertainty becomes the primary risk multiplier. The company's margin profile is no longer just a function of operational efficiency, but a complex equation of unknown contractual variables that could potentially any margin profile for the business.

F-35 Challenges

The risks associated with individual contract performance are no better illustrated by the F-35 program, which remains the single most important part of Lockheed Martin's business. Performance of the F-35 program has been a major driver of Lockheed's stock price for the year. A more stable outlook triggered a rise in the share price, only for Q3 to introduce more risks.

The source of the issue in the F-35 program is its ability to deliver a new software package, TR3, to the aircraft. While the company has commented that deliveries will increase to 180 aircraft through a mixture of inventory and new production, the problems have not been solved. Currently, Lockheed can only deliver a truncated software version limited to training operations, with full combat capabilities contingent on complex multi-system testing. Compounding this technical challenge is a separate unresolved supplier relationships threaten to delay critical production lots, potentially pushing key orders into 2025. There is a pathway to better performance on F-35, but this outlook is not reliable, and this program's performance is important enough to impact the company's overall growth.

The numbers tell a stark story. Lockheed has outlined that delays to the Lot 18 and 19 negotiations would push $2 billion of sales into 2025 with associated impacts to profit and $1 billion of free cash flow. Should this revenue be lost, this would mean an 11% and 3% reduction to Q4 and FY24 revenue estimates, respectively. FCF would also be reduced by 16% on a FY basis. On the other hand, Lockheed has estimated that the current drag on FCF from TR-3 related shortfalls amounts to $600 million, which is 9.6% of FCF, with recovery only expected over several years. These financial dynamics illustrate that the balance of risk around the F-35 is skewed to the downside, with a material negative impact still possible.

Uncertain Strategy

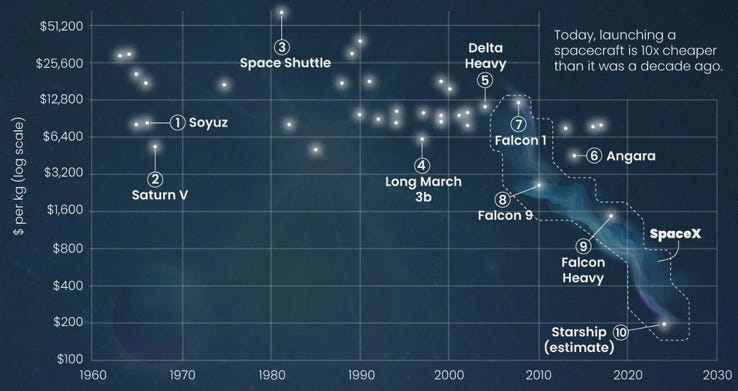

Recent news flow in the wider defense industry and the incoming Trump administration also raise questions about Lockheed's long-term strategy. As defense spending contracts and capabilities expand, each advanced system like the F-35 becomes a microcosm of the failure of the US defence industry to break out of a linear-cost-capability relationship. There is a growing perception that companies like Lockheed Martin could be vulnerable to potential tech start-ups entering into the defense industry and delivering radically lower-cost alternatives. The SpaceX model looms as a strategic warning—radical cost restructuring is no longer a theoretical possibility, but an emerging competitive challenge to companies like Lockheed Martin.

US Combat Aircraft Price, 1920-2018

Space launch costs per kg, 1960-2024

These concerns are best exemplified by the Air Force's Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program. The CCA is the Air Force's effort to deploy an autonomous drone to work in combination with the F-35 to jointly complete missions. The initial tranche of the program was awarded to two non-prime contractors, Anduril and Kratos.

Commentators have seen this as the first example of start-up defense contractors out-competing primes such as Lockheed Martin for such a significant defense contract. However, there are some important factors to discuss about the CCA contract as the significance of this contract loss is less significant than it would appear.

Firstly, the CCA contract itself is not fully complete, with the possibility that Lockheed will still play a part in the contract. Anduril and Kratos have been selected for increment 1 and the initial production contract of 100 units. However, the Air Force is also planning for an Increment 2 of the program, likely featuring another more complicated drone platform to fulfill different requirements. Lockheed's CEO clearly feels confident about the company's ability to compete further.

“Increment 2 is going to be -- targeted to be fieldable combat-ready, scalable design and production of the uncrewed teaming half of the system. So, we are fully dedicated to that. Like I said, we have Skunk Works working on both the parent and the child, if you will, when it comes to all CCA concepts and Increment 2 is going to be really where we're, I think, most competitive because we can show that we can control these vehicles with today's technology already at scale”

As the initial increment of the CCA is designed to be a less capable, cheaper system, it is less aligned with Lockheed's core competency of delivering large, highly complex, sophisticated systems. Further, in my view, there is nothing truly disruptive about the systems from Anduril and Kratos. Anduril's Fury drone was the result of an acquisition, with its development funded by the Air Force and is only 10-15% cheaper than solutions designed by the primes. Kratos GA-ASI was developed out of a previous Air Force development project called Skyborg. Neither represent a radically new approach to developing for DoD contracts, therefore they should be viewed in the same way as Lockheed losing out on any other contract.

The presence of more startups within the defence ecosystem may also coexist with Lockheed's long-term strategy. One outlined by CEO Jim Taiclet as a recent security conference.

Taiclet's vision seems to encompass both a strategic pivot and organizational change: transforming from a prime defence contractor to an also infrastructural platform for innovation. In my view this vision mirrors the telecom industry's evolution—not as a direct innovator, but as the foundational layer enabling technological disruption. This also seems logically given his previous roll was running a Telecom’s company

This strategy would be both interesting and precarious. By positioning itself as technological infrastructure, Lockheed acknowledges its structural limitations while creating a potential future adaptation mechanism. Yet, the approach introduces critical uncertainties for investors: Will infrastructure investment erode the company's historically robust 30% return on invested capital? Can cost-plus contract economics survive this fundamental restructuring? Is a period of capex required to build out networking assets?

Impact on the investment case

In my opinion, Q3 has been difficult to look beyond. The investment case for Lockheed has become largely dependent on limited fundamentals, limited visibility, and binary outcomes. Supply chain resolution, geopolitical defence spending shifts, and development timelines on the TR-3 issues are all potential event I have limited insight on or ability to analyse. The increase of capital into the US defense industry attracting more capital (and this competition) and an unclear long-term strategy also change the company long-term value proposition. Ultimately, I feel a c5% FCF no longer compensates for all this a Lockheed is now a source of cash in the portfolio.